Ever wondered where Swans go in the Winter? Where do they migrate to? OR, do they just battle the cold? Do some prefer it?

Well, we’ve decided to answer this question, at least regarding the most common species of swans you might come across in North America and Europe.

But first, here’s the quick answer about where Swans go in Winter, then we’ll get into some more detail…

Where do Swans Go in Winter? In October and November, about 520 to 650 species of swans that nest in the United States go to the south to spend their winters in milder climes. They remain during winter where they survive the winter months with sufficient food sources. They leave before the water in rivers and lakes freeze.

But what about other areas of the globe? And other swan migrating habits? Well, read in for more information…

Swans are graceful birds and the largest waterfowl species with a long neck, heavy body, and big feet. Most swans belong to the genus Cygnus. Swans are in fact mostly migratory birds.

Swan migrating flight formation

Like other migratory birds, swans fly in diagonal formation or a “V” formation. One swan acts as a leader and leads the flock. His or her job is to push through the air, which in turn makes flying easier for the rest of the swans in the flock.

As one bird gets tired another bird takes its place, swans take turns leading the flock. Swans fly at great heights, for example, Tundra swans fly at 6,000 to 8,000 feet, at a speed of 50 to 60 mph.

North American swans

The two main species of swan native to North America are the Trumpeter swan and Tundra swan. Other species include Bewick swan and Whistling swans (both split from Tundra Swan), Black swan, Whooper swan, and Mute swan,

Two swans, species trumpeter swans, and tundra swans look alike from a distance. Male trumpeter swans weigh up to 28 pounds and are considered one of the world’s largest water birds.

photo taken by Maga-chan

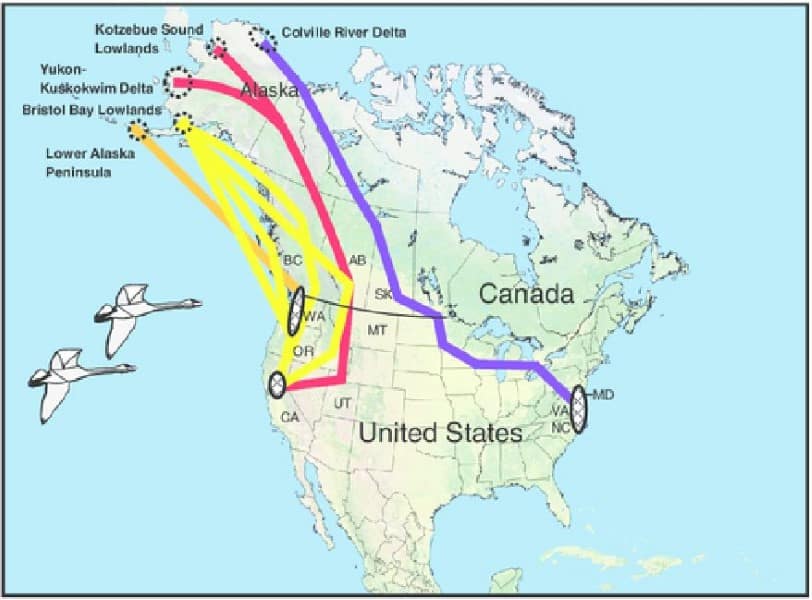

Tundra swans, also known as whistling swan, are less than two-thirds the size of a trumpeter. Eastern and western populations of both species follow different migration routes.

A large concentration of trumpeter swans winters on Vancouver Island. Trumpeter swans from Alaska winter near coastal waters from Cordova south to the Columbia River, in Washington.

More than 95,000 swans land in the Chesapeake Bay on America’s East Coast by November, a few weeks later, more swans gather in North Carolina.

Their migrations can overlap areas where trumpeter swans have been nesting or wintering. Eastern tundra swans migrate across the continent to winter on the Atlantic coast. The western population of tundra swans migrates to wintering grounds from Southern British Columbia to Central California.

Swan migration annual pattern for North America

British and European swans

Bewick and Whooper swans are found in Britain. These birds fly thousands of kilometers each year, to and from their breeding grounds in the arctic.

They migrate for only one reason; to take advantage of the very short but extremely productive summers in the Arctic tundra, where they breed.

Many of these swans then return south to spend their winters in mild climates. Between October and November, Bewick swans leave their Arctic breeding ground and migrate to winter in the coastal lowlands of northern Europe.

During their journey, they stop and rest in areas like Estonia, Lake Onega, and the White Sea. Whooper swans’ migration journey depends on the harshness of weather. Birds from western Iceland, choose western Scotland and Ireland as their wintering grounds while those from eastern Iceland winter in the rest of Scotland.

Mute swans, despite their name, are anything but mute. Adults are usually silent but make hiss, barks and rattling sounds. They can be easily distinguished from the tundra swans by its neck.

The neck of the Mute swan is not held straight but rather in a lovely S-shaped curve. Their bills are bright orange and black bills. This species is not native to North America but was brought over in the 1900s.

Mute swans in Europe may migrate to the Middle East in winter. Birds of North America typically do not migrate, even if ice generally develops, they stay wherever open water is available. Mute swans do not mind staying in Northern areas year-round if there is the availability of food in abundance or the birds are fed from supplemental feeders.

Young swans are knowns as cygnets. Young swans stay with their parents for about a year or two. During this time, cygnets learn a lot of skills from their parents such as migration routes. Some swans stay with their parents right up until they’re ready to choose their own mates.

Birds in the UK are resident birds, so they do not generally migrate. The estimated resident bird population in the UK is 28,000 to 30,000 adults. Juvenile birds migrate with their parents.

There are many instances where birds fly solo and still use the same route for migration. It seems that they sense the Earth’s magnetic field and use it to navigate. They also make sure to stick to the right route by adjusting their path using the position of the sun and the stars.

Conclusions

I hope that was useful as an overview guide on where swans go to in the Winter? Or where Swans migrate to? Now when you see a swan, just think about how many thousands of miles it it may have flown, just to get to that spot …the same spot every year – amazing!